Can there be trust in tech without commitment?

The proliferation of digital technology and its embedding in the everyday of home, work and leisure has brought to the fore concerns about their impact and harmful consequences. Further, we are constantly reminded about security, with Social Engineering and ransomware being significant threats, while identity theft continues to loom. Indeed, security is used as an argument for the proliferation of surveillance cameras, whilst efficiency and productivity are reasons for monitoring people in the workplace. However, there is concern that this is at the cost of privacy, especially in the workplace. Which invites the question of trust, and do we trust the technology we are working with. We increasingly hear about the need to “trust in technology”, given the potentially disruptive nature of newer forms of digital technologies. However, what is trust and what are its implications, especially for the workplace?

What is trust and do we trust technology?

I have previously defined trust as:

The willingness to be vulnerable to someone or something, with the unquestioned belief that this vulnerability will not be abused either deliberately or unintentionally.

This definition reveals trust as a relational concept. In other words, if there is trust there must be something else. This something else is commitment. Whilst trust is about exposing oneself to the potential of being harmed by another in the belief that the other will not harm you, commitment is the effort made by the other to not cause harm to oneself. This has implications for our engagement with the “other” that goes by the name of technology. This invites questions.

The first is whether we trust technology and those providing it.

The recent Edelman Special Report reveals there are many aspects to whether we trust technology, including what we perceive as digital technology. For example, we are more distrusting of social media viewed as a digital technology, with misinformation and deepfakes being significant worries. Given this focus on data, one significant concern relates to the use of digital data and privacy, particularly if related to technologies from foreign companies with governments that are neither trusted in terms of their data protection legislation nor how they would use personal data. These concerns about privacy could be alleviated if there is more personal control over the collection and use of data, greater transparency about how data is collected and guarantees that data will not be shared with the government.

More generally, the report reveals that lack of trust reduces the propensity to adopt new technologies. To enhance trust, the most impactful action is to communicate both positive and negative impacts. On the positive side, there is a perception that it can both improve the workplace and contribute to big social challenges. In contrast, over half of respondents have concerns about technology, such as AI, displacing human workers in the workplace. In response, there is a strong view that tech companies should contribute to the reskilling of those displaced by their technologies. This brings into focus the values of digital companies, especially the digital giants.

Technology companies are seen as less competent and less ethical in developed markets.

The second question asks what is commitment and from whom?

The juxtaposition of trust, commitment, is the effort to maintain a long-term relationship. It invokes such issues as openness, honesty, sensitivity to the needs of the other, and shared gain and pain. Core to this is communication, without which, the trust-commitment relationship breaks down. If we are being asked to trust technology, then we are expecting the technology to not cause harm. However, is it sensible to say that the technology has agency and is “committed”? Whilst the knife can kill, it helps us in the everyday to cut things. The knife affords different possibilities for use, but its use determines its impact. Instead, the focus should be upon the commitment of those providing and applying the technology.

A more holist perspective

The third question focuses on the trust-commitment relationship and what drives commitment.

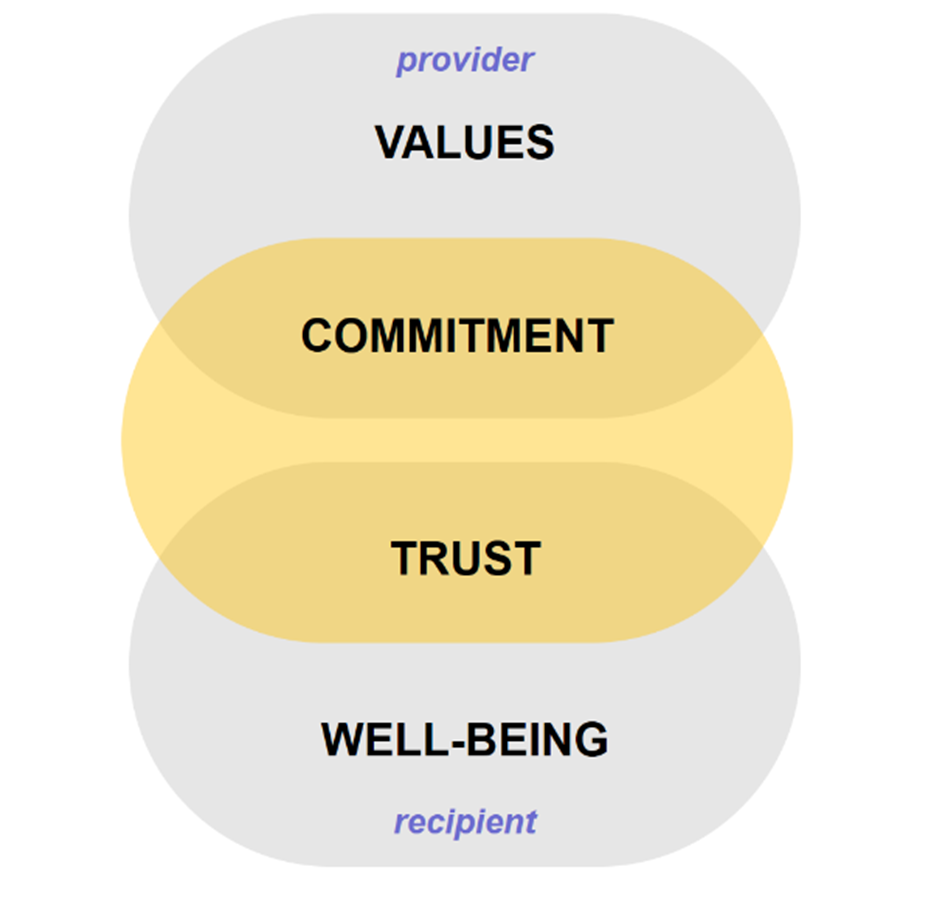

Elsewhere, I have argued that the trust-commitment relationship interfaces between the values of the technology provider and the well-being of the recipient. In other words, trust-commitment bridges the technology “values – well-being” complex. Values, irrespective of whether held by a person or an organization, are the principles or moral standards that shape behavior and impact well-being. If we hold the principle that we do not wish to harm people, then we will make the effort to ensure that we do not harm people, with the consequence that people will trust us. If this logic is extended to the principles of helping people and caring for the environment, then their well-being may be improved.

Implications for the workplace

The technology “values – well-being” complex has ramifications for the way organizations deploy new technologies in the workplace, particularly emerging forms of digital technology and the changes that result. The underlying rationale of the employer, as the provider of the technology in the workplace, is the assumed expectation that it will improve business and operational performance in the form of productivity, efficiency, agility, or creativity. As recipients of the impact of their deployment, an employee can view new technologies as a threat in the form of the changes they bring and how they affect personal well-being, whether this is the need and anxiety associated with reskilling or the fear and uncertainty of facing redundancy.

For example, since the middle of the twentieth century, the introduction of automation into the workplace has raised fears about worker redundancy, but one option has been to reskill and redeploy the employee. Moreover, new forms of work have emerged creating new work opportunities. Nevertheless, the disruptive nature of the fusion of emerging technologies such as robots, AI 5G and sensors, is resurfacing these concerns, inviting the question of how much reskilling and redeployment will be possible and whether there will be a mass of people who are unemployable. This is a debate relating to the longer-term bigger picture and the role of governments in handling this.

To return to the individual organization, in simple terms, how new technologies are handled boils down to employer values, intent, approach to deployment, and how this translates into concern for employee well-being. However, job displacement is just one aspect of these newer forms of technology. The game-changer of recent digital technologies is the recent explosion in the amount of data generated, with its doubling shortening from every two years to every 12 hours by 2025. Issues with data include that it can be invisible, and we can be unthinking about the data we are providing about ourselves. With more and more devices generating data, used not only by humans but also by different technologies, debates about the collection, use, storage, sharing, trading, theft and misuse of this data are flourishing.

Sensors in the workplace

Whilst data can be related to all manner of issues, one sensitive issue is data that relates to people and sensors in the workplace. Imagine the scenario whereby your access to a workplace building is controlled by facial recognition technology. Your employer requires you to download an app onto your smartphone, which provides you with a dashboard providing you with role-specific information, including alerts as well as conferencing facilities. Recognizing that you are on site, it displays the hot desks that are free, highlighting the ones you tend to prefer. Access to a particularly secure part of the building is enabled using a retina eye scan. Cameras monitor whether you give any unauthorized person access to this secure area. An RFID card provides access to printer facilities as well as can make payments for the drink and snack dispensing machines. In addition to this personal digital technology, “security” cameras are distributed throughout the building.

Does this scenario raise any concerns? What if, being a technophile, the CEO has the idea that chip implants might be a simpler way to control all this?

Perhaps the dominant argument for having such a digital presence is security/safety with convenience as a potential added benefit. However, the volume of data collected collectively builds a digital profile of the person (a data body) which raises issues about privacy. Whilst the employee may consent to all this data collection, is this freely given? Would refusal imply restrictions or loss of employment? Likewise, what would refusal of the smartphone app on a personal smartphone lead to? Alternatively, if a company smartphone is provided with the app, is it switched off outside work time? Some smartphone apps can remotely switch on cameras and microphones and record the moment without those in the vicinity of the smartphone knowing. What private situations can be covertly recorded? To add is the issue of who owns the data and what rights a person has over his/her data body.

Following data collection, then the next issue concerns how the data is used. What possibilities does the data afford for providing information about a person? For example, biometric data, which is unique to that person, contains information that enables a person to be tracked. Facial recognition surveillance can reveal movements and contacts. Retina scanning can potentially pick up health issues or substance abuse. Given the volume of real-time data collection, data analytics and artificial intelligence can then profile each person, highlight particular behaviors and rank people according to performance or other metrics, thus affecting benefits and rewards.

Further, data bodies have the quality of mobility affording the possibility of being shared, with government agencies, or transacted for economic gain.

The worst scenario concerns cybersecurity, raising the issue of how much attention is given to ensuring the security of all devices, both the obvious, such as laptops and datacentres, as well as the less obvious such as sensors. This is particularly relevant to personal data and raises the need for responsible attention to the protection of data.

Data is like the knife example. The intent underpinning the collection, use, and security of the data is what’s at issue. On the one hand, there are companies that explicitly state that their intent and practices are to have a positive impact on people and communities, including their employees. Data empowers.

Likewise, there are other organizations, where there is not this concern and the emphasis is on minimizing costs and maximizing profit, irrespective of the implications. Data becomes a means of control. This is against the backdrop of privacy and data protection legislation such as the variety of related laws in the U.S. and Europe’s GDPR. If this is the situation today, what about tomorrow? Especially since there is another, more data-intensive emerging technology that is currently receiving much attention. This is the metaverse.

The metaverse

The metaverse does not currently exist, though there is much hype about it. The metaverse promises an immersive experience, which extends virtual reality from being a solo experience to being a shared experience involving many others. Within this virtual space, it is postulated we will be able to do much of what we can do in real reality. One manifestation of this is the industrial metaverse, which will be a space that allows people to interact, with problem-solving being one possible activity. People distributed around the world can come together to examine problems and work out how to deal with them.

However, as a digital space then one concern again relates to the data that can be harvested. As an immersive experience, what we see, hear and say, and with whom can be recorded and analyzed. Our data body captures everything about our engagement in the metaverse. Does this amplify the insights that can be established about each participant in the metaverse? But, by whom? The employer? The metaverse host? The platform provider? The infrastructure providers? Or all the above?

So where does this leave us?

All this pessimism might raise the question of whether I am a Luddite.

My response is an emphatic NO!!!!!!

Technology, especially newer forms offer great promise to improve every aspect of life and help deal with the world’s big challenges. It will transform the workplace. However, newer forms of technology have another side to them that urges caution. This side manifests in data. Data is not neutral.

Data is a fuel that can enhance the empowerment and democratization of the person in the street and in the workplace. It can inform, enhance understanding and hence improve the quality of decision-making.

However, on the other hand, data can also be a fuel to consolidate control by creating an inequitable relationship between employer and employee. We might give consent for the collection, use, and everything else relating to data, but is our consent freely given, or is it conditional upon getting the job offer or retaining our job? We might be told about how data is collected and used, but are we told everything? One aspect of the data harvested is that it can reveal a person’s characteristics that the person is unaware of. Whilst these insights can be used to develop the person, they can also be used to explicitly or tacitly enforce compliance.

This returns us back to the aforementioned “values – well-being” complex and the importance of the trust commitment relationship. The expectation of trust in technology is unrealistic unless there is a commitment by those who are to be trusted to make the effort to not cause harm, either intentionally or accidentally. This raises the question of who is to be trusted. From the viewpoint of the employee, there is the proximity of the workplace employer and the commitment of the employer to protect the employee, whether it is with job security, respect for privacy or the desire to empower and enrich the work experience. Perhaps this simplifies as, digital technologies, in particular, are a complex configuration of many visible and invisible technological elements, which are open to disruption and exploitation by the unscrupulous. This highlights the importance of values as shaping moralities to guide the providers of all the technological elements. Underpinning these values is a concern for the well-being of employees but would this not translate into a care for the well-being of humanity and, by default, the environment, since humanity is dependent on our environment if we are to survive?

To conclude, we may preach the need for trust in technology, but as a relational concept, it brings to the fore commitment, grounded in values, without which trust is unachievable. For trust to be achievable, the commitment needs to be explicit, which invites a call for all organizations to express their commitment to not harm in a “code of commitment”. If all organizations have a “code of commitment” might this then lead to the much-vaunted trust in technology?