The discontent of today’s workforce presages a new era of work culture

What are the most critical aspects of work culture from the perspective of workers? Perhaps we can start by asking workers why they want to quit their jobs and triangulate on the factors in organizations that drive them away.

What We Learned In The Big Quit

Perhaps the most important single data point about work today is this: in 2021, a record-breaking 47.4 million U.S. workers quit their jobs voluntarily.

Conceivably we can learn from the pandemic and the ‘great resignation’. The reasons people say they quit could provide a blueprint for better work culture.

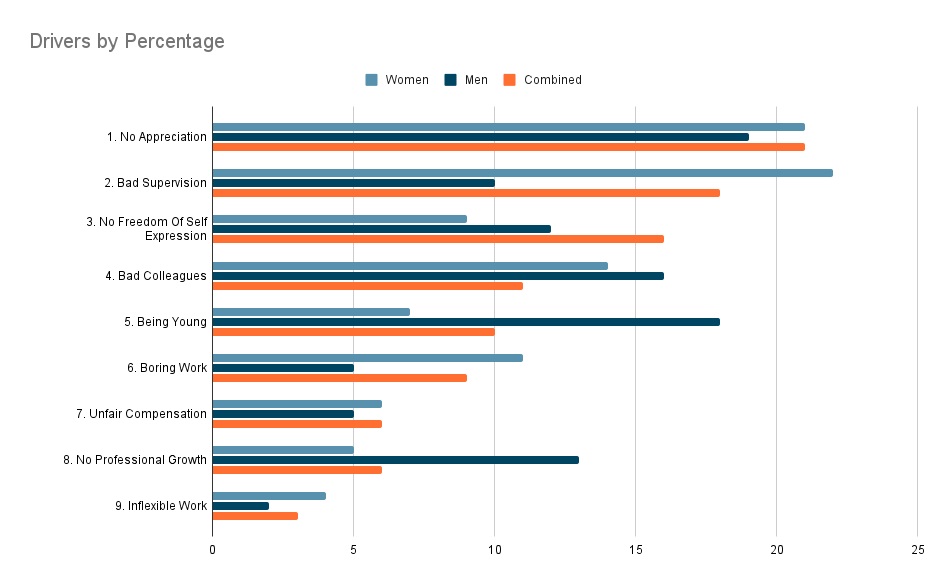

According to a recent PlanBeyond survey of 1,000 full-time employees between 18 and 64, here are the top reasons driving people to quit their jobs:

Note: ‘inflexible work’ includes scheduling and work location flexibility, and the desire to work outside the office has become a major issue.

In Employers believe workplace culture has improved during pandemic, but workers disagree, Alan Goforth points a finger at the disparity between what executives and the rank-and-file think about Covid’s impact on organizational culture:

“Employers and employees agree that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on workplace culture. They disagree, however, on whether the resulting cultural changes have been positive.

Seventy-two percent of executives (vice president and above) believe their overall organizational culture has improved since the beginning of the pandemic, according to a new survey by the Society for Human Resource Management. Far fewer HR professionals (21%) and workers (14%) agree. HR professionals and other employees indicate issues with communication, altered workloads, and employees voluntarily leaving their companies as primary reasons for negative changes in workplace culture during the pandemic. “

Even though this research is from SHRM, it seems that HR folks are deluding themselves about perceptions of corporate communication:

“Almost all HR professionals (99%) agree that they encourage a culture of open and transparent communication, but 27% of employees disagree.“

However this research confirms that many leave their jobs because of a bad relationship with their manager:

“More than half of employees who have left a job in the past five years because of workplace culture indicated it was because of a relationship with their manager.“

And why are managers perceived as the root cause for so many departures?

“More than one-third of working Americans indicated that their manager does not know how to lead a team, and 26% of people managers said their workplace does not provide leadership training.“

Humu, the work software company, surveyed 240 full-time employees recently, and uncovered some major findings:

- “79% of participants said that they would leave their job for one that better supports their wellbeing. And when asked about the key factors that affect their job satisfaction, “work-life balance” was at the top of the list: 76% respondents ranked it as one of the top three things that determine whether or not they like their job.

- When asked to list the attribute that they want most in a manager, employees’ top response was “support for work-life balance” (61%) followed by “flexible work arrangements” (39%). Employees who have a manager that makes an effort to help them combat burnout are a whopping 13 times more likely to be satisfied with their manager. Unsurprisingly, 58% of employees agreed that the biggest contributor to burnout is having a bad manager.

- Another (often overlooked) part of supporting employees’ wellbeing is providing them with sufficient growth and development opportunities. We find that individuals whose manager fails to give them useful and frequent feedback are 2.6x more likely to feel burnt out and 5x more likely to consider quitting. On the other hand, employees with managers that regularly take time to give them feedback are 3.6x more likely to feel motivated by their work. This aligns with past Humu research that showed that employees who don’t have enough growth opportunities at work are 7.9x more eager to quit.“

The Problem and Limits of Meta-Analysis

The surveys discussed above bring to light something more fundamental than the findings that form their motivation. Since the various researchers start with different perspectives and target different participants, the many findings are difficult — if not impossible — to assimilate in a uniform way. This indicates a core problem with attempting to synthesize a coherent whole from the many constituent parts. It is nothing like fitting together a jigsaw puzzle but is more like the wall shown in crime labs where red string relates various bits of evidence pinned to a corkboard.

Looking across a battery of survey results I have started to ask these questions:

- If a majority of the surveys have a group of questions in common, does that mean those questions reflect the central issues? Or does that instead reflect groupthink and low diversity of perspectives?

- Alternatively, is it possible that what we will look back on as the most important questions are those that are less commonly shared by researchers, and which may represent the emergence of a new paradigm for thinking about the problem?

If we run aground on the limits of meta-analysis, what is the recourse?

My sense is that we need to start with an aspirational model of work: how it could be at some not-too-distant time in the future, based on countering the negatives in modern work culture. Instead of approaching these problems statistically or ethnographically, instead, we could start with an idealized work culture where the various cultural pillars support each other and collectively represent an evolution away from an out-of-balance culture, one where the needs of all are sacrificed for the wants of a few. Therefore, I will attempt to characterize a possible future work culture, one that balances the needs of all. Let’s start with the first point of imbalance: companies put too little emphasis on organizational learning.

The Learning Organization

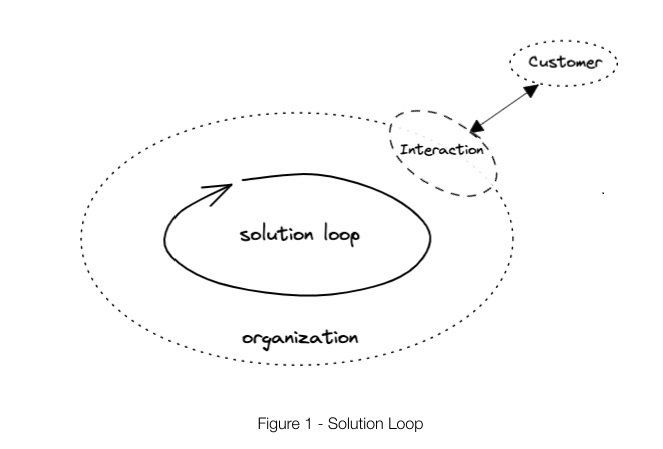

The primary loop of any organization is delivering value to customers, either through products or services: the solutions loop. This is the domain of strategic business operations. Businesses create solutions and bring them to market, interacting with customers, and gaining feedback from those interactions.

But in order to improve product and service offerings, that feedback — and other salient information from the market, customers, and competitors — there has to be a second loop where those data and insights are assimilated: a learning loop.

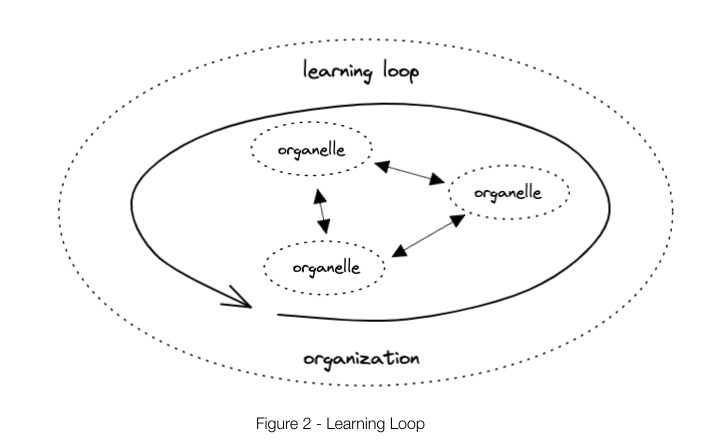

Where intelligence about customer needs and market forces can be channeled to improve the company’s delivery of value and to develop a deeper knowledge of critical domains, at the individual, group, and organizational levels. In this chart, I refer to ‘organelles’, which are smaller units in the larger organization, whether teams, divisions, or whatever organization scheme the company uses.

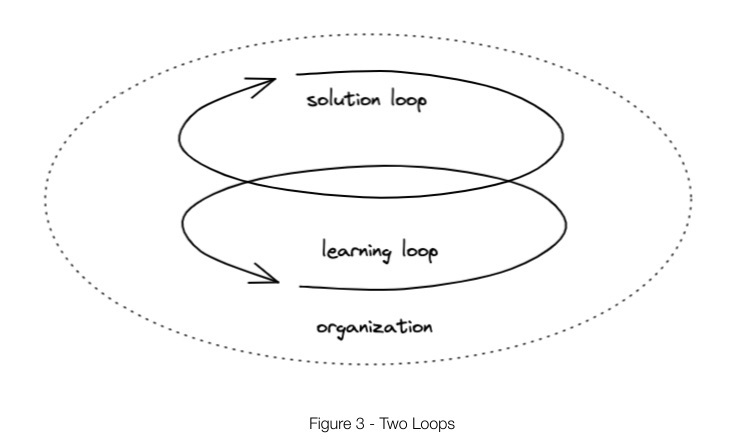

In practice, the two loops are running in parallel, and people across the company are involved in both, learning and delivering value at more or less the same time. Note the give-and-take arrows between the organelles in figure 2, which represent sharing of ideas, insights, and information among people and groups across the network and the company. Some of that learning energy is directed toward improving solutions, but some is dedicated to improving the culture at work. What is the right balance?

Out-Of-Balance: Linear Culture

Consider the mismatch in understanding between the managers and rank-and-file workers about work culture improvement, mentioned earlier, where 72% of senior executives thought culture had improved during the pandemic, compared with 14% of workers. Relative to learning about the mindset and condition of workers, these results make it clear that the senior executives must be cycling in different loops, perhaps loops involving only other management. If those executives were spending time listening to the concerns of workers, perhaps there wouldn’t be a 50% skew in that SHRM survey result.

A company culture that overemphasizes solutions or delivering value — productivity — over learning is accumulating a cultural debt, an imbalance that slows personal development and downplays the importance of organizational learning. Let’s call this Linear Culture.

In Figure 3, I’ve drawn the two loops as having the same velocity and weight: a company in balance. However, that is seldom the case. The greatest evidence of that comes from survey data: companies in balance would not have such high degrees of worker dissatisfaction. It is companies that overemphasize productivity to the detriment of other considerations that are seen as out of balance, obsessed with the linear processes around solutions, and putting those considerations ahead of people. However, it is not just an imbalance of learning and productivity: there is a range of factors that make up an in-balance work culture.

In-Balance: Emergent Culture

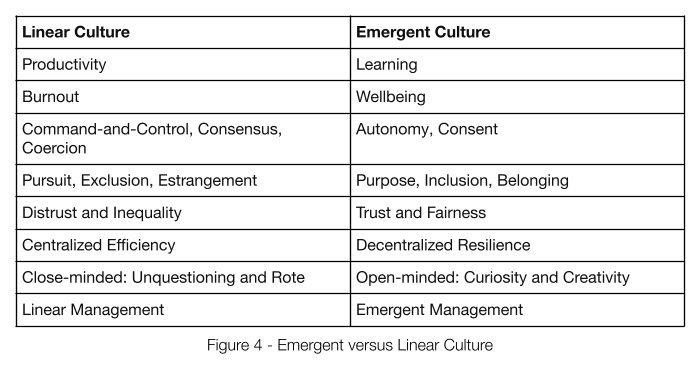

More than the relative weight and velocity of the two loops, there is a short set of work culture attributes that distinguish linear culture from what balanced companies embody: let’s call those in-balance exemplars Emergent Culture. Both ‘emergent’ in the sense of ‘appearing at this time’, and in the deeper sense of being defined by emergent properties arising from the interplay of the elements of the system, such as resilience, adaptability, and ethics.

Learning

Emergent companies weigh learning gained through delivering value to customers as equal to the delivery of goods or services. Therefore, they structure their work architecture to match this.

Here are some questions that could be used to determine if companies are learning-centered:

- Is the company actively supporting a culture of learning, both for individuals and groups?

- How is the company learning to be more agile and delivering innovative solutions?

- How does the company support self-development and personal advancement? Are individuals limited to only learning in areas immediately applicable to their current role?

- Does the company just pay lip service to learning, or is it explicitly built into work projects, projects, and organizational design?

- How much work time can an individual dedicate to learning?

- Is there a chief learning officer, or equivalent?

Many companies fail to invest in learning since they are afraid people will leave the company once better trained, and as a result, they chronically underinvest in the future of the company.

Wellbeing

Emergent companies put the wellbeing of all workers ahead of other considerations, even learning and delivering value to customers.

Jim Harter of Gallup connected the dots between workers’ perception of employers and wellbeing:

“This finding is critical for organizations because employees who strongly agree that their employer cares about their overall wellbeing, in comparison to others, are:

- 69% less likely to actively search for a new job

- 71% less likely to report experiencing a lot of burnout

- five times more likely to strongly advocate for their company as a place to work and to strongly agree they trust the leadership of their organization

- three times more likely to be engaged at work

- 36% more likely to be thriving in their overall lives.“

Gallup’s research has also found that teams who are most likely to feel the organization cares about their wellbeing achieve higher customer engagement, profitability, productivity, lower turnover, and fewer safety incidents.

A company that isn’t actively working toward a wellbeing-centric culture is — at least implicitly — condoning burnout and a variety of mental and physical illnesses.

Autonomy and Consent

Emergent companies endorse high levels of autonomy for individuals and organelles. This is not limited to tactical decision-making involving customers and production.

As just one highly topical example, emergent companies expect individuals and organelles to determine how to accomplish their work: when, where, and how. And at the most advanced: with whom.

Companies that assert employees whose work could be accomplished offsite nevertheless must perform that work in the company’s offices — especially involving unreimbursed commuting — are discounting their employee’s freedom of choice, and perpetuating linear domineering of workers.

Emergent group decision-making can take many forms, but in general, operates on the principle of consent as opposed to coercion or consensus.

- Consensus–decisions made by a group but where all must agree to the proposed solution.

- Coercion–decisions made by authority, often removed from the context of the decision.

- Consent–decisions made when no group members raise critical objections to a proposal, and if they do, the proposer must work to resolve the objections.

Both consensus and coercion are both slow in practice and can be used to stifle innovation and autonomy.

Consent-centered organizations display greater resilience and adapt more quickly to rapidly changing conditions: exactly the world we find ourselves in today. While there are situations where consensus is called for, coercion is almost always the worst approach… but widely practiced.

Purpose, Inclusion, Belonging

As shown in the table in figure 4, linear companies implicitly put organizational goals above the needs of workers. The goals of pursuit, exclusion, and estrangement subordinate people’s desires for purpose, inclusion, and belonging:

Pursuit and Purpose–The company’s implicit and explicit aims — such as gaining a certain percentage of a market, or developing life-saving medical products for cancer patients are company pursuits. Whether noble or merchantile, companies generally expect workers to subsume their personal goals to align with the company’s pursuits.

In an emergent organization, one of the company’s pursuits is to create an environment where people are not forced to sideline their personal goals for the sake of the company: the two interests must be balanced, just as in the case of learning versus productivity.

Inclusion–Donald Sull and his colleagues researched 1.3 million Glassdoor reviews of a sample of large U.S. companies, called the Culture500. One overarching result?

“Seven of the 20 most powerful predictors of a negative culture rating relate to how well Culture 500 companies encourage the representation of diverse groups of employees and whether they are treated fairly, made to feel welcome, and included in key decisions. Collectively, this cluster of topics is the most powerful predictor of whether employees view their organization’s culture as toxic.“

The five factors that determine if a culture is inclusive are gender, race, sexual identity and orientation, disability, and age. All of these ‘rank in the top decile of strongest predictors of a toxic culture’.

Note: their analysis leads to indirect support of the argument I made earlier in The Problem and Limits of Meta-Analysis:

“None of the diversity, equity, and inclusion topics emerged among the top predictors of a company’s overall culture in our previous analysis using collective employee ratings. This absence highlights the danger of measuring corporate culture exclusively in aggregate terms. If leaders focus on the average review of corporate culture among employees, they may miss issues that affect a small number of employees in profound ways. Respect, for example, is mentioned 30 times more frequently in employee reviews than LGBTQ equity is, but both topics have the same impact on an employee’s view of culture when they are discussed negatively in a review.“

An emergent culture is inclusive of all people, irrespective of gender, race, sexual identity and orientation, disability, and age.

Belonging–One of the most powerful drivers in life is to gain the respect of those that we respect. This is a major component of belongingness at work, which is a deeply social aspect of work culture. Other social aspects of work — like having friends at work — have been shown to increase the bonds of engagement in the workplace.

Perhaps it’s counterintuitive but marginalized employees — those who are at the receiving end of an exclusionary culture — have reported a greater sense of belonging when working ‘remotely’, basically avoiding the microaggressions that seem to occur most commonly from in-office interactions.

An emergent culture would foster high levels of belonging, and provide time and context for social connections to occur.

Trust and Fairness

Business today has trust problems. One critical example: lack of trust in (and respect for) their supervisor is the number one influencer for women to consider quitting. Not so much for men, who are perhaps less vulnerable.

The two range from fair pay (especially for women and minorities), to fair opportunities (for example, blind resumes and interviews), to explicit statements of company ethics and policies to deal with unfair treatment, such as the factors listed in Belonging, above. The U.S. ranked 20th in equal opportunities for women according to The Economist, as just one data point.

As just one modern example of a conflict in trust, many companies deploy surveillance ‘spyware’ on workers’ computers to monitor time spent in work applications or away from the desktop, and institute check-in/check-out monitoring as part of a back-to-the-office policy. These do not send a message of trust.

An emergent company promotes a ‘first trust, then trustworthiness’ ethical system.

Decentralized Resilience

I wrote an essay on Resilience recently, and made this observation:

“The difference lies between thinking about a business as a set of linear processes to be optimized for speed and cost versus considering a business as an ecology—a circular network of interdependent competing and cooperating organisms—from which the capacity for resilience may emerge when the conditions are right.“

Today’s linear companies centralize many activities that could help adapt to a rapidly changing world, as opposed to distributing intelligence-gathering and innovation out to the edges of the organization. This slows down effective response and reduces the autonomy of those closest to the customer.

Again, from that essay,

“instead of seeking to make the company into the leanest possible linear system—a strategy of reduction—leaders could instead aspire to looser, wider connections across the company, and an intentional diminishing of downward control. These are the hallmarks of deep resilience.“

And the profile of an emergent culture.

Open-minded: Curiosity and Creativity

Linear cultures — despite their espoused desire for innovation — are deeply creativity-averse. Rigid and close-minded cultures see creativity as ‘noxious and disruptive’.

Likewise, Kashdan and his colleagues found that linear leaders often ‘think that letting employees follow their curiosity will lead to a costly mess’ and ‘although people list creativity as a goal, they frequently reject creative ideas when actually presented with them’. Since curiosity and creativity often challenge the status quo and do not always yield immediately useful insights, leaders are reluctant to entertain the exploration of new ideas.

The linear mindset is all about productivity and efficiency, and too often managers will see only wasted time and woolgathering in creative activities of the curious. Note also that curiosity declines the longer we are in a job.

An emergent culture looks to harness curiosity and creativity instead of stamping it out. This involves taking on more of the mindset of researchers, artists, and inventors, and accepting the uncertainties of deep innovation.

Emergent Management

“Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.” | Bertold Brecht, *Life of Galileo*

The role of management, or more fundamentally, the purpose of management changes significantly in the shift from linear to emergent culture and operations.

At the organizational level, this shift involves a change in focus of what senior managers do, which increasingly can be thought of as gardening instead of architecture. Emergent management, at the highest aggregated level, is about creating and stewarding an environment in which the many elements of an emergent organization are balanced. Instead of answering the hardest questions, the emergent leader makes sure the hardest questions are asked, and that the organization is prepared to answer them.

Emergent management has a second meaning, at the more personal level. One of the most important skills in modern organizations is the capacity to step up to lead a project, an initiative, or some other group activity as needed, and once that need has been met, to be willing to step down from that role.

These two sorts of leadership are the same in one sense, although the timeframes may differ.

Any management in an emergent culture is grounded in the concept of subsidiarity: the organization should accede to the individuals what they can accomplish, to small groups only what individuals cannot, and to larger groups only what small groups cannot.

An emergent culture will produce individuals that assume management roles from a sense of duty and commitment rather than a desire for power or control, and upon a foundation of subsidiarity. As Brecht suggests, we are best off when our societies do not rely on heroes.

The Transition to Emergent Culture

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” | Buckminster Fuller

The transition from linear to emergent culture is already happening.

In one case, individuals decide to leave their current firm because of linear negatives and move to another for emergent positives. People are selecting companies closer to an emergent — even if unarticulated — ideal.

In another case, change agents can push for effective and lasting change in organizations. Activists self-select and act as ‘positive deviants’ who introduce new ways to do things, new ways of thinking and actively reject outmoded linear techniques and principles. The linear organization’s immune system will naturally hinder efforts to shift the culture toward emergence, but change can be made. And occasionally farsighted leaders can use their power to rework the ethical principles of a business toward emergent order and away from the past.

There is a growing movement of thinkers, practitioners, and activists who promote emergent models of work culture (under a variety of labels), along with the idea that a greater-than-the-company emergent work culture can influence and transform individual companies. These visionaries are having a decided impact, and their numbers are growing. The collective goal — perhaps not always expressed — is to build a new model for work culture, as Fuller tells us, that makes the existing model obsolete.

Will these three threads lead to something lasting, or is it another management fad? Just remember Margaret Mead’s Two Nevers:

- Never depend upon institutions or government to solve any problem. All social movements are founded by, guided by, motivated and seen through by the passion of individuals.

- Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed, citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.