Why should I be in the office? It’s not ‘because I told you to.’ That’s not the answer. – Tom Naratil, the president of UBS in the Americas

Each technological revolution brings with it, not only a full revamping of the productive structure, but eventually a transformation of the institutions of governance, of society, and even of ideology and culture. – Carlota Perez

Introduction

Everything has been changed by the pandemic, since a crisis is a time when everyone reconsiders what previously seemed like bedrock and that’s what’s happening, now. One of the questions now dominating the discourse around work is the workweek: particularly, where will people work, and how much time will they spend there?

I am revealing my thesis in the quotes above. Tom Narati declares that going into the office has to have a purpose greater than pleasing management. And Carlota Perez paints a broader landscape but can be applied in this context in a direct way: now that we can in fact work anywhere — because of widespread high bandwidth and a host of modern communication and collaboration tools — eventually, a revolution will occur. One that reaches into every facet of work and business, transforming even ideology and culture.

What is the workweek? How did it become a ‘9-5, five days a week in the office’ deal, and where will it end up once the pandemic recedes?

The Past and Present of the Workweek

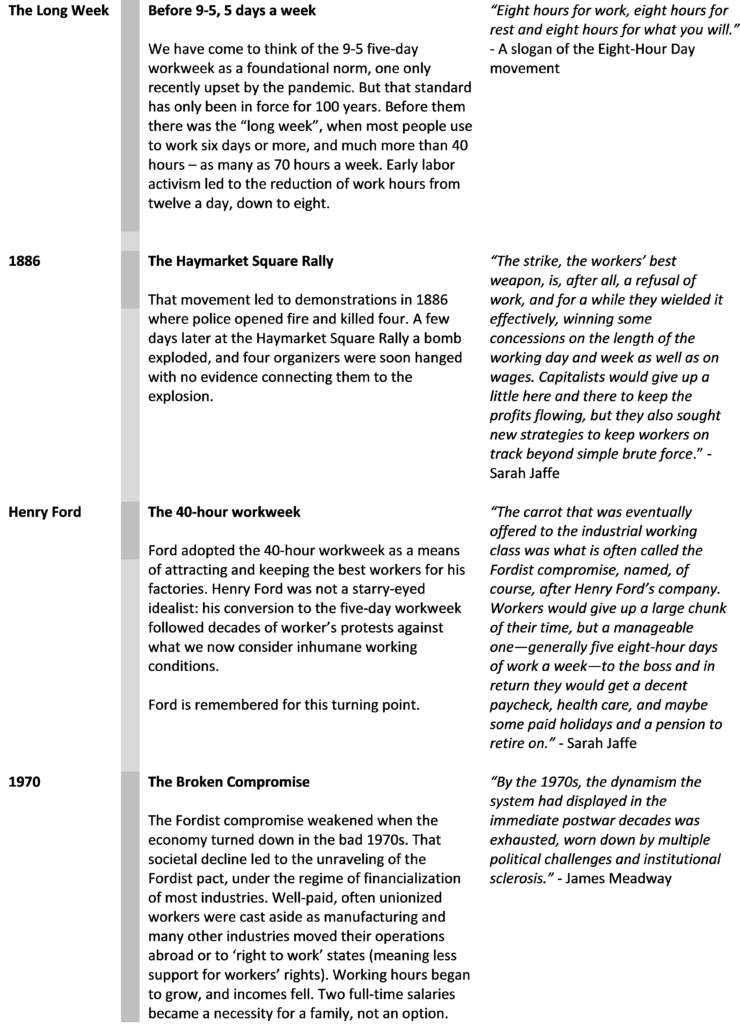

We have come to think of the 9-5 five-day workweek as a foundational norm, one only recently upset by the pandemic. But that standard has only been in force for 100 years. Here’s a timeline of events leading to the present.

A Timeline for the Workweek

Despite the relapse of the historical trend, today’s white-collar knowledge workers are still the beneficiaries of a five-day workweek, established principally for a blue-collar workforce who today are less likely to be covered by the now-tattered pact, not to mention gig economy workers who have never had such protections.

One thing to take away is this: the history of the work week has been — until quite recently — a slow war between employers who in general sought longer workdays and weeks and workers who pushed for shortening them. Although not generally discussed in those terms, what is happening today, in 2022, must be seen as a continuation of that dynamic, not as something novel precipitated by the pandemic.

But the pandemic has led to a rupture in the fabric of work, and it’s unlikely that we will return to ‘normal’.

Day by Day, Week by Week: The Future of the Workweek

There are a large number of trends at play when we take a close look at the ongoing transformation of the workweek.

The Pandemic Meteor: The Hive and the Net

The most obvious trend — more like a giant meteor hitting the surface of the Earth than a mere trend — has been the impact of the pandemic on the status quo ante: where in the “before times” the average worker would commute to the office five days a week, and work (nominally) nine to five in close proximity with their team members and managers, and sharing office space, corridors, and elevators with other workers with whom they seldom interacted with directly. Let’s call this the Hive model of work, where coworkers could talk face-to-face, share physical space, and smell each other’s pheromones.

The average commute time in the US was around 50 minutes round-trip, according to the US Census Bureau. So, working from home translates into an hour of found time, plus the time not spent prepping for work, picking up the dry cleaning, and so on.

For many, this was the first time ever they worked outside the Hive.

According to Tanza Loudenbach:

An additional 20 minutes of commuting per day has the same negative effect on job satisfaction as receiving a 19% pay cut. That is to say, spending more time standing on a crowded train or sitting in mind-numbing traffic can make you feel just as bad as earning less money, even if you aren’t.

The pandemic led to many companies sending workers home, and a mad scramble to adapt to a suddenly distributed world of work.

Instead of the Hive, we adopted the Net model of work, where the formerly clustered workers now worked individually, in their own residences, and everyone relied overwhelmingly on computer-mediated communications in place of the mix of face-to-face interaction in the Hive. They could work in their PJs, take naps and long walks, spend more time with family and non-work friends, and shift work from the conventional nine to five to times that suited them personally.

But with the waning of the pandemic, many organizations are now pushing for a return to the office: for example, Elon Musk declared that he expects Tesla and SpaceX office workers in the office at least 40 hours per week. Apple made clear that it expected most workers back in the office as soon as the pandemic abated, which was met by strong pushback, with some employees demanding that the company stop treating them like school children.

Other companies have adapted to a changing world of work and are incorporating some of the Net model of work:

Some companies, like Airbnb, have recently told their employees they never have to return to the office; others, like Goldman Sachs, where workers are back five days a week, remain zealous about the benefits of in-person work. But many businesses are in the fuzzy realm of hybrid work. BlackRock, for example, asks employees to come to the office three days, and Citigroup now asks for at least two. And plenty of hybrid workplaces are still trying to decide how many days employees should report back to their desks, while finding that attendance is something challenging to track or enforce.

“The word of the day is chaos,” said Becky Frankiewicz, U.S. president of ManpowerGroup, a global staffing agency with more than 4,500 offices. “I had a Canadian C.E.O. ask me probably three weeks ago — ‘Becky, we opened the offices and no one came back, what do we do now?’”

The Aftershocks

The arguments offered for working in the Hive are many, as recently laid out by Peggy Noonan, who worries about the decline of ‘office life’ and all that comes from it in The Lonely Office Is Bad for America:

- My guess is the end of the office will lead to a decline in professionalism across the board. You learn things in the hall from the old veteran. You understand she’s watching your progress, and you want to come through with your excellence.

- There will likely, in each company and organization, be a decline in a sense of mission. A diluting of company spirit looks to me inevitable. Spirit, mission—they come from people and are established and imparted through being together, sharing a particular space, talking to each other spontaneously and privately, encouraging and correcting.

- It is possible working at home is changing the nature of professional ambition.

Noonan doesn’t include the counterarguments, like the fact that productivity is up, and workers who work remotely are more engaged with their companies, in general, even prior to the pandemic. And she, and others touting RTO, seem to ignore the perspectives of workers who want out of the Hive.

As I discussed in The case for giving people time to do deep work, many workers’ principal responsibility is doing individual work, for which they need quiet and solitude. This is Paul Graham’s notion of Maker Time versus Manager’s Time:

When extroverted managers compel others—especially introverted makers—to operate around highly synchronous manager’s time, the makers lose both autonomy and the necessary continuity of their work, rendering them less effective and less engaged.

Now that managers want workers back in the office, they have to face the fact that commuting is either work, or a tax, or both. And the question is, who is paying? Many in management would like to go back to the status quo ante, but that doesn’t seem right. And it’s certainly no incentive.

But businesses are accepting the fact that the majority of people don’t want to work 100% in the Hive and will quit if compelled to. Companies are getting the message.

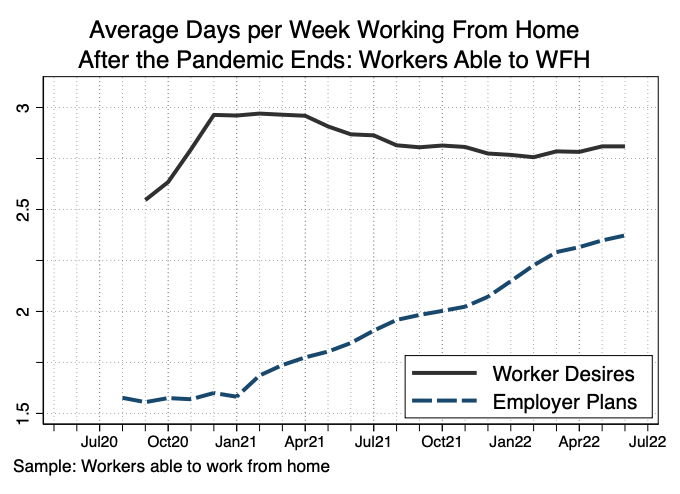

There is an underlying trend, an undertow, that I have called ‘minimal viable office‘: in a world organized around the Net model of work, people would go into the office as little as possible. As researchers Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis reported in April, expectations of employers and employees seem to be converging toward a hybrid standard for those who can do their jobs outside the office: more than 2.75 (round up to three?) days of non-Hive work per week (Figure 1).

The aftershocks following this transformation of work are continuing, and where it will all fall out in the months and years to come is yet to be seen, but here’s what we can be certain of:

- There will not be a wholesale return to the Hive, as many are espousing, like Peggy Noonan and Elon Musk, but we may see a gradient running from 100% Hive to 100% Net, with something like a bell curve distribution: a very small number at each end, and the great majority falling in the hybrid middle.

- Companies will get better at Net-work. It should not be surprising that the shift is hard since most people had very little or no experience in this new Net way of work, especially managers.

- As a new generation of management emerges (and an older one leaves the fray), they will be more accepting of and adept with Net management. They will not have a dozen years of 100% Hive instincts baked in, like much of today’s leadership.

What is Emerging as the New Workweek?

It’s only an island when you look at it from the water. – The character Chief Brody in Jaws

The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to have lasting, non-superficial changes on how work is structured, managed and performed, but at this point — while the pandemic is still with us — it is unclear what the post-pandemic world of work will look like.

But we can learn a lesson from Chief Brody — a small insight — even at this point when we are still in the midst of the ongoing changes: It’s only remote when looked at from the office, a Hive-centric point of view.

Much of the rhetoric about the new workweek has been a reaction to how nettiness is different from hiveyness. Put another way: most terminology is based on treating working away from the office as ‘remote’. But viewed from home, headquarters looks remote. As Chief Brody points out, it’s a matter of perspective.

So let’s define some terms for clarity, I am using a five-day workweek as the baseline, but the movement toward a four-day workweek is also growing. I’ll touch on that next.

Here’s a set of terms that might characterize today’s while-the-pandemic-is-still-with-us understanding, and based on the individual’s viewpoint: how many trips do I have to take to the Hive per week?

- Five days: this was the old normal, and didn’t have a name per se, just ‘going to work’. I am proposing ‘onsite work‘ (which may be more palatable than 100% Hive). Note that many jobs are largely onsite, like healthcare, manufacturing, construction, retail, hospitality, and logistics, and many of those folks don’t work in offices, so ‘in-office work’ fails as a general term.

- Then we have three scales of increasingly offsite, nettified work:

- Two or three days onsite: this is the “new normal” for most knowledge workers. Generally called ‘hybrid work‘.

- Less than two days but more than zero onsite: for some jobs, a day per week or month may be enough to allow for regular interaction and face-to-face cooperative work. This might be grouped with ‘hybrid work’ but is more generally called ‘remote work’.

- Zero days onsite: this is often called ‘fully remote work‘ and is generally associated with companies that have no offices to visit. This is the apotheosis of Net-work.

Shortening The Workweek: The Four-Day Workweek

An alternative to the emerging norm of the flexible model of hybrid work is a fixed four-day work week: one that is like the older baseline of a five-day onsite workweek, but with one less day of work. Some attempts are based on four ten-hour days, while others are 32 hours: four 8-hour days, which are more popular, unsurprisingly.

Perhaps the most tracked experiments prior to the pandemic were in New Zealand and Japan.

Four-day workweeks made headlines around the world in the spring of 2018, when Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand trust management company, announced a 20% gain in employee productivity and a 45% increase in employee work-life balance after a trial of paying people their regular salary for working four days. Last October, the company made the policy permanent.

A much-referenced pre-pandemic trial of the concept was undertaken by Microsoft in 2019 in Japan, which led to a 40% reported rise in productivity. But that experiment did not only change the length of the workweek but other factors, as well:

Because of the shorter workweek, the company also put its meetings on a diet. The standard duration for a meeting was slashed from 60 minutes to 30 — an approach that was adopted for nearly half of all meetings. In a related cut, standard attendance at those sessions was capped at five employees.

These additional tweaks to the standard operating procedure are also the responses that we are seeing in the hybrid work model, now, after companies have adapted to the pandemic.

The attractiveness of the productivity boost latent in a four-day workweek — which can benefit onsite and offsite workers, alike — has attracted many other pilots: including other companies in New Zealand, and others in Belgium, Ireland, U.K., U.S.A., Scotland, Wales, Iceland, and many others. The results have been largely positive:

Several pilot studies have been conducted to gauge the impact of a shortened workweek. The largest until now was held in Iceland between 2015 and 2019, with 2,500 public sector workers taking part. This trial was considered a success, showing positive results for a range of wellbeing indicators including stress, burnout, health and work-life balance. Unlike the current trials in the UK, however, the Iceland study tested reduced working hours, but not specifically the four-day workweek.

The UK experiment includes more than 3,300 employees at 70 companies who will get an extra day off every week for six months, without a reduction in pay. The programme is being led by a civil society organisation, 4 Day Week Global, a think tank, Autonomy, and the 4 Day Week UK Campaign, in partnership with Boston College and the universities of Cambridge and Oxford. It seeks to investigate how the adjusted workweek affects productivity, employee wellbeing, gender equality and the environment.

The 4 Day Week Global initiative is also responsible for pilots elsewhere, including in Australia, Canada and the USA.

The range of these studies makes analysis challenging, but there seems to be a general sense that these trials have demonstrated that a four-day workweek is possible, and it leads to both higher productivity and greater perceived well-being. They have been popular with the workers involved.

Conclusions: Where Will It Wind Up?

In the largest cities in America, the move away from Hive-work has been profound. A May survey conducted by the New York City Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) showed stark numbers:

The MTA said that a survey of 160 employers in May showed just 8 percent of workers have returned to offices in Manhattan five days a week; that 28 percent are still working remotely full-time; and that 78 percent of workplaces allow employees to split their time between the office and home.

There is some evidence that things are more like the pre-pandemic Hive model of work in smaller cities:

More than two years into the pandemic, American corporate workplaces have splintered. Some are nearly as full as they were before Covid-19 struck; others sit abandoned, printers switched off and Keurig cups collecting dust. Workers in America’s midsize and small cities have returned to the office in far greater numbers than those in the biggest U.S. cities. Some executives in large cities are hoping they’ll catch up, though they’ve been impeded by safety and health concerns about mass transit commutes, as well as competitive job markets where employees are more likely to call the shots.[3]

In small cities — those with populations under 300,000 — the share of paid, full days worked from home dropped to 27 percent this spring from around 42 percent in October 2020. In the 10 largest U.S. cities, days worked from home shifted to roughly 38 percent from 50 percent in that same period, according to a team of researchers at Stanford and other institutions.

Those researchers refer to the 12 largest American cities as ‘superstars’, and those locales — like New York City — are where the Net way of work has become most deeply rooted.

We could see a great polarization in this case as in so many others in The U.S. and across the world.

The large cities — which drive the majority of nearly all countries’ GDP, innovation, and culture — have already shifted to a Net model of work, with a distribution of styles. Some proportion of workers continues with 100% onsite work, including those that must be onsite, like retail, medical, public service, and hospitality workers. However, the knowledge workers in these cities are distributed across various forms of hybrid work, differing only in the number of days they go into the office.

The smaller cities and rural areas seem to be falling back into the older back-into-the-office model, although with a greater degree in flexibility and some degree of hybrid, such as working from home a day a week.

We may witness a shift toward a four-day workweek in both of these cases, but that movement seems to have less traction in the U.S., where recovery from the pandemic continues week by week, month by month, and the dominant story remains the tension between working in the Hive, or in the new world of Net-work.

I expect that imbalance between larger and smaller cities to continue, absent some new tipping point, like a resurgence of Covid, some other pandemic, or some other factor. I had thought that a surge in inflation and a steep spike in gasoline prices would have influenced more toward offsite work, but it hasn’t seemed to: at least not yet.

Over a long enough period of time, however, historians and students of culture have determined that the diffusion of innovations runs from areas of the highest population — where innovation is highest — outward to less populated areas. In the long run, the Net-work model is likely to grow, then, and the Hive way of work will decline. We may just have to wait for a generation of business leaders to retire — or die — before we cross that divide.

There does not seem to be a modern-day Ford, stepping forward with a new compact between business and workers, setting a new norm, and forcing others to get aboard the bandwagon. Not Elon Musk, who wants everyone back in the office. Perhaps Brian Chesky, the chief of Airbnb, could be the heir to Ford’s mantle, since he proclaimed in May that ‘the office as we know it is over’, and established policies that allow Airbnb employees to live and work anywhere without a change in pay. Chesky may be the nettiest of all.