So much about work depends on the pace of alternating between noise and silence.

“Nothing has changed human nature more than the loss of silence.” – Max Picard

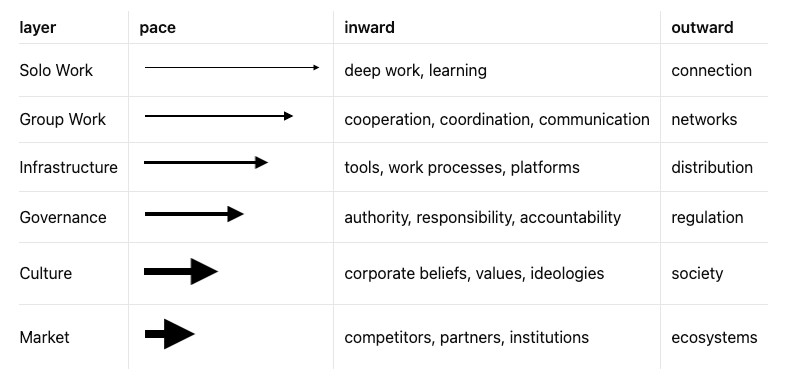

In The Pace Layers of Work article, I introduced Stewart Brand’s model of Pace Layers and recontextualized it into the world of work instead of his target context: civilizations. The core idea is that change is mediated by layers in civilizations or businesses, those at the top change more quickly than those lower in the stack of layers.

Any cultural change in business comes from a cascade of faster and smaller-scale changes in higher layers. So, adoption of new ways of work by individuals percolates to groups, which influences infrastructure, which shifts patterns of governance, and finally impacts the foundational culture of the business.

The extrinsic force of the pandemic has certainly introduced a broad spectrum of changes at the three top layers of the Pace Layers of work. Consider the shift to dispersed work with higher reliance on team communication technologies and the cascade of secondary effects like meeting fatigue and the great resignation. The question is whether these top-layer changes will ultimately be reflected in long-term shifts in governance and culture. The behavior of many senior leaders signals a resistance to any deep changes, but what will come remains to be seen.

What if downshifting business communications to incorporate a greater proportion of asynchronous communication could be a profound catalyst for change in business culture. What if this shift not only raised productivity, increased engagement, and better decision-making, but also spurred second-order impacts, like an increase in resilience across the business, and a greater openness to adopting new ideas, practices, and technologies?

Here, I explore research about the most tangible benefits from shifting the ratio of silence-to-noise, asynchronous-to-synchronous, in work communications. Through that, I will demonstrate the principle that changing the pace of how we work holds the promise of a foundational change in work culture, and how changing pace may be the fastest and surest route to outpacing change.

The Silence-to-Noise Ratio in Work

Silence is not just the absence of noise, although often positioned as such. The value of the time spent working in silence is what we do with it. And first, we must understand how silence and noise interact, and how we think about them.

There is research that shows humans have two neuronal systems for parsing speech. Counter to what was previously thought, we use one set of neurons for listening to speech, and a second that is activated by the silence between words, to find the places where talking stops.

“Silence is no longer today an autonomous world of its own; it is simply the place into which noise has not yet penetrated.” – Max Picard

We’ll see that keeping out the noise is the key to improvements in productivity, decision-making, and creativity that can’t necessarily be achieved otherwise.

Why Time—and Silence—Is So Important

Someone once countered the saying ‘time is money’ by pointing out time is a limited resource: you only have so much of it, and can’t acquire more, unlike money. Therefore, time is more important than money.

But we really should reconsider the implicit assertion that time is homogeneous. It isn’t. Different sorts of time vary widely in value. An hour saved by skipping a meeting is worth a great deal if it is applied to something of higher value, like closing the door to read a colleague’s comments on a product plan and which sparks a new insight. But that regained hour could be lost in the rubble of emails and work chat, leading to little advantage.

We need to learn to balance time with other people—which tends toward noise, but still can be high value—against time alone, which tends toward silence. So, there are two types of time.

Maker’s Time, Manager’s Time

Paul Graham, the venture capitalist behind Y Combinator, wrote a massively influential post in 2009, dividing the world of work in two: people live on Manager’s Time or on Maker’s Time:

“There are two types of schedule, which I’ll call the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule. The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour. […] Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.” – Paul Graham

But managers exert a strong gravitational force and will naturally pull makers into the tight circles of Manager’s Time, fragmenting the large blocks of time needed to actually accomplish deep work, as Cal Newport calls it.

“Deep work is the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task.” – Cal Newport

Newport characterized deep work as a skill, not a state of mind: a skill mostly based on working in solitude behind a closed door.

Rob Cross and his colleagues established that ‘collaborative work’—time spent on email, chat, texting, phone, and video calls—has grown at least 50% over the past decade, with an additional upward spike in the pandemic, including “… people spending more time each week in shorter and more fragmented meetings, with voice and video call times doubling and IM traffic increasing by 65%. And to make matters worse, collaboration demands are moving further into the evening and are beginning earlier in the morning.”

Virginia Heffernan in Meet is Murder asked Graham if he still believed in the duality of Maker and Manager time that he had spelled out seven years earlier, and yes, he did.

Graham then described his ideal meeting, conjuring a congenial fantasy “There are no more than four or five participants, and they know and trust one another. They go rapidly through a list of open questions while doing something else, like eating lunch. There are no presentations. No one is trying to impress anyone. They are all eager to leave and get back to work.”

The distinction between Maker’s Time and Manager’s time is the tension between two forms of time orientation. People alternate between asynchronous and synchronous work, diving deep below the waves to focus individually, and then returning to the surface to perhaps communicate with the team or team members in real-time. The question is how much time should you spend on each side of the interface?

Logically, the answer lies on a point somewhere between two ends of the dimension between 100% asynchronous and 100% synchronous. There is a great deal of evidence that many kinds of synchronous communication are a waste of time, like Cross’s collaboration overload and the organizational drag from wasted meetings.

There is also the difference between extroverts and introverts to consider. Introverts need quiet alone-time to recharge after social interactions, while extroverts gain energy from interaction.

So introverts—who are often the most gifted and creative workers—need more silence and closed-door time than extroverts. Associated with that, introverts process information differently, and are less likely to command time in meetings and other social settings. They are disadvantaged in those settings.

Graham’s point is that when extroverted managers compel others—especially introverted makers—to operate around highly synchronous manager’s time, the makers lose both autonomy and the necessary continuity of their work, rendering them less effective and less engaged.

Tech Leans Toward ‘Asynch-First’

Because of the pandemic and the enforced transition to remote work, a heightened level of attention has been directed toward the best ways to communicate and coordinate when most are not working face-to-face. But many tech companies had been operating on an ‘asynch-first’ communication mode for years, in some cases driven by a dispersed model of operations; but other companies with a co-located, office-centric culture have also incorporated elements of asynchronous communications.

Jeff Bezos, in the early days of Amazon, instituted a ‘six-page narrative’ model to kickstart important meetings: “We don’t do PowerPoint (or any other slide-oriented) presentations at Amazon. Instead, we write narratively structured six-page memos. We silently read one at the beginning of each meeting in a kind of ‘study hall.’”

This approach avoids death-by-PowerPoint—a presenter drones on, and the group listens (or not)—replacing that with individuals reading the memo, making notes, thinking in silence: carving out alone-time in the context of a meeting. This is a slightly confounding example since at the same time it: a) reduces the time in the meeting often dominated by a one-to-many presentation in real-time and b) instead institutes a solitary reading of the memo by everyone in the room. In a way, this seems like an intermediate step toward something less real-time, where participants would read the memo prior to the meeting, asynchronously.

Jason Fried is the co-founder of collaboration company Basecamp, and the firm has a very strong orientation toward asynchronous, remote operations. A key part of that is moving away from face-time/real-time and relying on long-form writing for communication.

As he wrote a few years ago:

- Writing solidifies, chat dissolves. Substantial decisions start and end with an exchange of complete thoughts, not one-line-at-a-time jousts. If it’s important, critical, or fundamental, write it up, don’t chat it down.

- Speaking only helps who’s in the room, writing helps everyone. This includes people who couldn’t make it, or future employees who join years from now.

- Communication shouldn’t require scheduled synchronization. Calendars have nothing to do with communication. Writing, rather than speaking or meeting, is independent of schedule and far more direct.

- Write at the right time. Sharing something at 5pm may keep someone at work longer. You may have some spare time on a Sunday afternoon to write something, but putting it out there on Sunday may pull people back into work on the weekends. Early Monday morning communication may be buried by other things. There may not be a perfect time, but there’s certainly a wrong time. Keep that in mind when you hit send.

Fried’s arguments frame the philosophy behind ‘asynch-first’ operations, but he doesn’t sketch out how to get there.

Matt Mullenweg, the CEO of Automattic (the company behind WordPress, and also Simplenote and Tumblr), a fully distributed and asynch company, proposed a five-level maturity model that integrates remote work, autonomy, and asynchronous operations, and provides that missing framework for getting there. Here’s a brief summary:

- Level zero—jobs that require colocation, such as plumbers, firefighters, or massage therapists.

- Level one—companies that default to colocation and synchronous operations, without really attempting to move toward distributed, asynchronous work.

- Level two—companies that begin to grapple with—and benefit from—disconnecting work operations from colocation and synchronous operations. Mullenweg notes this is where many companies found themselves at the outset of the pandemic, and that they tend to recreate what they had been doing at the office, like video meetings instead of face-to-face meetings. This means workdays are full of interruptions, management worries about productivity, and workers are overloaded by communication demands.

- Level three—companies start to invest in equipment to support distributed work, like good at-home chairs, and decreasing impediments like clunky VPNs to access corporate resources. Level three companies invest so teams can come together a few weeks a year.

- Level four—at this stage of maturity, companies evaluate workers by what they accomplish, not on ‘how or when they produce it’. Level fours transition to ‘better—perhaps slower, but more deliberate—decision-making’. These companies begin to hire people regardless of physical location. Meetings are elevated by the use of synchronous and asynchronous communication tools, with greater attention to pre- and post-meeting planning and follow-through (as with Bezos six-page memos). People are given greater autonomy to accomplish their work their way.

- Level five—Mullenweg says level five is unobtainable but represents the aspirational goal of highest degrees of autonomy, outcomes-based evaluation, and asynchronous operations.

I believe a maturity model Like Mullenweg’s is helpful even though it commingles a number of trends that often are considered independently, especially by those that would like to remain—or return—to level one or two operationally.

Like any maturity model, the organization needs to decide on what level they are currently and what they aspire to become. Then they can decide which cultural and practical behaviors fit their maturity goals and make the necessary changes.

Communicating in Bursts is Best

Christoph Riedl and Anita Williams Woolley researched remote team performance and discovered ‘bursty’ communications are best:

“Human communication is naturally “bursty,” in that it involves periods of high activity followed by periods of little to none. Our research suggests that such bursts of rapid-fire communications, with longer periods of silence in between, are hallmarks of successful teams. Those silent periods are when team members often form and develop their ideas — deep work that may generate the next steps in a project or the solution to a challenge faced by the group. Bursts, in turn, help to focus energy, develop ideas, and achieve closure on specific questions, thus enabling team members to move on to the next challenge. […] they should align their work routines and then communicate in short periods when everybody can respond rapidly and attentively. That’s the route to higher performance.”

The authors contrast being ‘bursty’ with the often-cited serendipity from chance interactions in the office.

The bottom line: Worry less about sparking creativity and connection through watercooler-style interactions in the physical world, and focus more on facilitating bursty communication.

Decision Making: Intermittently Communicating Is Best

How do the best decisions get made? Our intuition might lead us to think getting a bunch of knowledgeable people in a room and supplied with the facts will lead naturally to good decisions. But Ethan Berstein and a group of researchers sought to find out if that was indeed the best way to go. They discovered that ‘always on’ leads to worse results than an alternation of asynchronous individual work and exploration of the problem and periodic group interaction, sharing individual ideas and insights.

From prior research, the researchers anticipated that the groups whose members never interacted would be the most creative, coming up with the largest number of unique solutions—including some of the best and some of the worst—and a high level of variation that sprang from their working alone. In short, they expected the isolated individuals to produce a few fantastic solutions but, as a group, a low average quality of solution due to the variation. That proved to be the case.

The researchers also anticipated that the groups whose members constantly interacted would produce a higher average quality of solution, but fail to find the very best solutions as often. In other words, they expected the constantly interacting groups’ solutions to be less variable but at the cost of being more mediocre. That proved to be the case as well.

But here’s where the researchers found something completely new: Groups whose members interacted only intermittently preserved the best of both worlds, rather than succumbing to the worst. These groups had an average quality of solution that was nearly identical to those groups that interacted constantly, yet they preserved enough variation to find some of the best solutions, too.

Looking Ahead: Taking Time—and Silence—Back

Here is a combination of recommendations for companies to adopt asynchronous-by-default work in the upper tiers of their pace layers, and to start to drive it down into core work culture.

Shift to asynchronous communication to the maximum extent possible and adopt a model of intermittent and bursty synchronous communication to augment it, not to control it.

Looked at from a pace layers perspective, this transition could take years—maybe a decade—to permeate a corporate culture if starting from a face-time, real-time starting point.

Consider time banking: many companies have seen great benefits from measuring how much time is consumed by synchronous communication (meetings, real-time chat, and video calls), and capping it. So, if a new meeting appears on your calendar, some other meeting has to go, or several others might have to be made shorter. A first step might be to create meetingless Mondays or Fridays or both, to clear time for deep work. Again, this could take years to affect the culture tier.

Get bursty, intermittent, and deep, and tool up accordingly. Riedl and Woolley express this well: “Whenever teams are apart physically in work settings, managers should work to develop burstiness, foster information diversity, establish periods of deep work without interruption, and tailor the use of audio and video technologies to meet the needs of particular interactions. Such practices will help drive remote teams’ performance in our emerging new normal.”

I believe we are moving into a post normal era of work, one that represents a break with historic ways of work, not an extrapolation of existing patterns: not just a new normal. Still, I concur with Riedl and Wooley’s mini manifesto, although pace layering means it might take a decade or more for these new norms to spread from top to bottom in individual companies, and across the greater work ecosystem, even in a world transformed by the pandemic.

We are in a time of great experimentation at the infrastructure pace level, with explosive innovation around tools, work processes, and platforms to support taking time and silence back. These are just the starting point for experimentation and adoption of new infrastructure to enact this shift in our perception and application of time and silence. Stewart Brand pointed out that change is hard because of inherent resilience of human culture, its gyroscopic capacity to resist change, even when it would be beneficial to all, because while ‘fast gets all the attention, slow has all the power’.