Governments need to plan now for the day automation makes many workplace skills obsolete.

WALLY KANKOWSKI OWNS a pool repair business in Florida and likes 12 creams in his McDonald’s coffee each morning. What he doesn’t like is the way the company is pushing him to place his order via a touchscreen kiosk instead of talking with counter staff, some of whom he has known for years. “The thing is knocking someone out of a job,” he says.

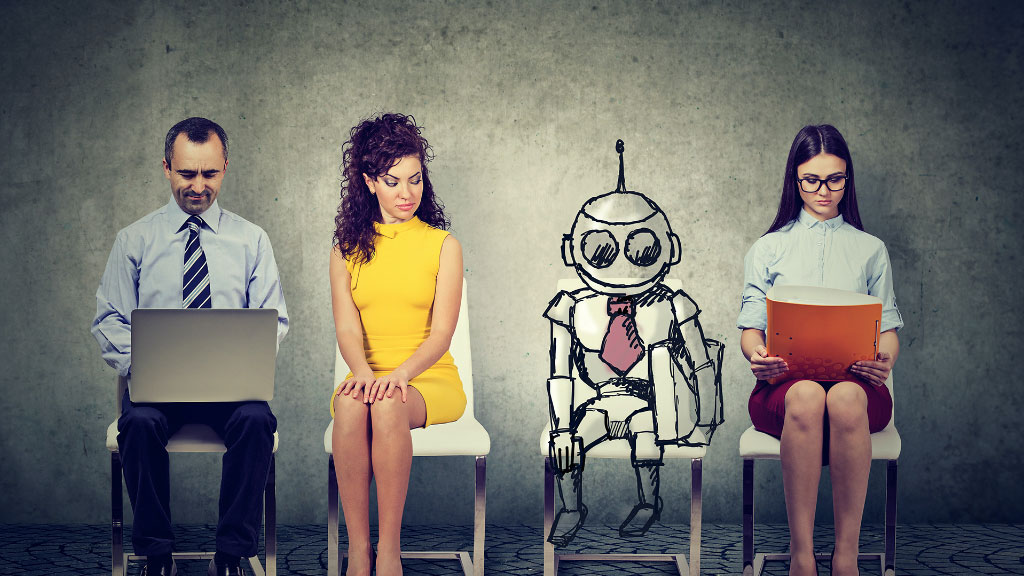

Wally is one of several humans who discuss the present and future of workplace automation in the seventh installment of the Sleepwalkers podcast, which offers an atlas of the artificial intelligence revolution. The episode explores how work and society will change as AI begins to take over more tasks that people currently do, whether in apple orchards or psychiatry offices.

Some of the portents are scary. Kai-Fu Lee, an AI investor and formerly Google’s top executive in China, warns that AI advances will be much more disruptive to workers than other recent technologies. He predicts that 40 percent of the world’s jobs will be lost to automation in the next 15 years.

“AI will make phenomenal companies and tycoons faster, and it will also displace jobs faster, than computers and the internet,” Lee says. He advises governments to start thinking now about how to support the large numbers of people who will be unable to work because automation has made their skills obsolete. “It’s going to be a serious matter for social stability,” he adds.

The episode also looks at how automation could be designed to assist humans, not replace them—and to narrow divisions in society, not widen them.

Toyota is working on autonomous driving technology designed to make driving safer and more fun, not replace the need for a driver altogether.

George Kantor from Carnegie Mellon University describes his hope that plant-breeding robots will help develop better crop varieties, easing the impacts of climate change and heading off humanitarian crises. “Better seeds means better crops, and that could ultimately lead to a more well-nourished world,” he says.

Kantor and Lee both argue that thinking about the positive outcomes of automation is necessary to fending off the bad ones. “Whether we point at a future that is utopia or dystopia, if everybody believes in it, then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Lee says. “I’d like to be part of that force which points toward a utopian direction, even though I fully recognize the possibility and risks of the negative ending.”