Missteps by corporations and institutions balancing the bottom line with employee well-being have led to a global pandemic of burnout, one that reaches into all aspects of life, at work and at home. Exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of productivity are seeping into every aspect of work.

Of all affected in the U.S., working mothers—as is so often the case—are being hit the hardest, due to their ‘second shift’ of childcare duties.

Before we can start to consider how to deal with burnout, we need to understand how it starts, how it harms us and our work, and how to recognize the preconditions that cause it. Only then can we consider how to burnout-proof our workplaces and help those harmed by this modern affliction.

There is also an intermediate set of symptoms, something well short of burnout, that psychologist Adam Grant discussed with his friends after two years of the pandemic:

“It wasn’t burnout—we still had energy. It wasn’t depression—we didn’t feel hopeless. We just felt somewhat joyless and aimless. It turns out there’s a name for that: languishing.”

“Languishing is a sense of stagnation and emptiness. It feels as if you’re muddling through your days, looking at your life through a foggy windshield. And it might be the dominant emotion of 2021.”

Grant characterized languishing as ‘the neglected middle child of mental health’, it dulls your ability to focus, saps motivation, and triples the likelihood that you will sidestep work.

And it could well be that languishing, if not ameliorated, can slip into something more threatening. Burnout has become so prevalent that mental health professionals are using the term post-pandemic stress disorder because of the similarities to post-traumatic stress disorder.

Many of us are experiencing trauma.

Burnout affects many

A huge swath of the population feel burned out: forty-two percent of U.S. women and 35% of U.S. men said they feel burned out often or almost always in 2021.

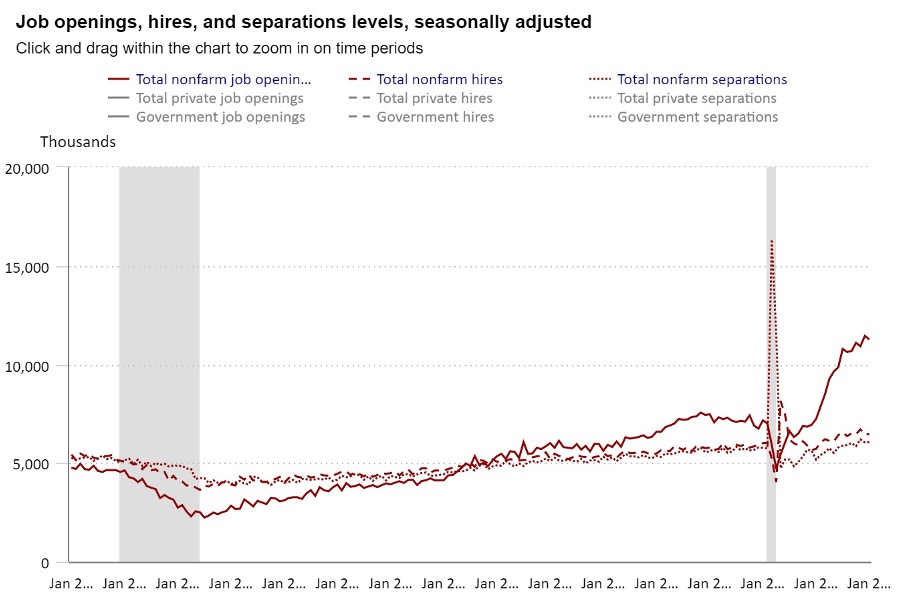

There is no doubt that burnout is a contributing factor to the ‘Great Resignation’, as Jamie DuCharme reports:

“Every month from April to August 2021, at least 2.5% of the American workforce quit their jobs. In August alone, more than 4.2 million people handed in their two weeks’ notice, according to federal statistics. So far, 2021 quit levels are about 10% to 15% higher than they were in record-setting 2019.”

Defining burnout

A group of organization psychologists led by Christina Maslach distilled the term job burnout:

“Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and is defined by the three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy.”

Let’s examine the three elements of burnout and their relationships:

Exhaustion—People who burn out generally start from a deep, unrelenting tiredness, but as Maslach points out:

“The fact that exhaustion is a necessary criterion for burnout does not mean it is sufficient. If one were to look at burnout out of context, and simply focus on the individual exhaustion component, one would lose sight of the phenomenon entirely.”

Exhaustion, in this context, goes beyond mere weariness. Because of the relationship people have with their work, exhaustion leads people to distance themselves emotionally and cognitively from their work, as a coping mechanism. This leads to depersonalization, an attempt to distance themselves from others in the workplace and losing the sense of connection at work.

Cynicism—As depersonalization becomes ingrained, it can grow into full-fledged cynicism, when coworkers, clients, or patients are viewed as ‘objects or problems more than people’. The relationship with exhaustion leading to cynicism is found consistently across burnout research. That team member making angry-sounding wisecracks about management may be showing signs of burnout.

Inefficacy—Beset by chronic, overwhelming demands that underlie exhaustion and cynicism can drain the sense of effectiveness at work. People find it difficult or impossible to maintain a sense of accomplishment, the third indicator of burnout.

It turns out that burnout scores (from testing) are fairly stable over time, ‘which supports the notion that burnout is a prolonged response to chronic job stressors’, and as such, builds up slowly and can only be moderated slowly, as well.

How people burn out

The shorthand for how people burn out:

Men are from cynical; women are from exhaustion.

The burnout behavioral patterns of men and women vary to a consistent degree. But in both cases, the end result is the same, exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy at work. But burnout goes beyond the “walls” of the office leading to disruption at home and socially, as well.

Age is a strong demographic indicator of the likelihood for burnout. Younger workers are more prone to burnout than those over 30 or 40, so more risk early in a career, which perhaps represents greater stress at that stage.

Men are solitary sufferers, much less likely to talk about their problems at work or elsewhere. As Jonathan Malesic writes:

“Men are about 40 percent less likely than women to seek counseling for any reason. And the well-documented crisis in male friendship means that many men have no one aside from their spouse or partner they feel they can open up with emotionally. Single men often have no one at all; when they burn out, they may do so alone.”

Our society has written different playbooks for men and women, and they don’t necessarily provide what’s best for those playing. Again, from Malesic:

“To address men’s burnout in particular, we have to acknowledge that consciously or not, our society still largely equates masculinity with being a stoical wage earner. Not all men view themselves this way, and even men who don’t are still susceptible to burnout.”

According to The Pew Research Center, in 2017, 71 percent of Americans thought “being able to support a family” was important to a man’s role as a good husband, while 32 percent said it was important to a woman as a good wife.

And this stoicism comes at the cost of a higher level of cynicism.

The stresses on women are different from those of men, and women react differently as well. Women are much more likely to discuss their problems with their spouses, friends, and coworkers: they are less stoic. However, in 2021, 42% of working women felt burned out all or mostly all of the time, 5% more than men. So, talking about burnout isn’t necessarily a curative.

Researcher Malesic cites a meta-analysis on burnout in which women on average scored higher than men on the exhaustion scale. Working mothers are saddled disproportionately with the so-called “second shift” of child care. Dr. Wendy Dean considers this a betrayal of working mothers, in some of the harshest criticism I’ve seen:

“This isn’t burnout—this is societal choice. It’s driving mothers to make decisions that nobody should ever have to make for their kids.”

Both mothers and fathers can suffer from parental burnout, where the stresses and strain of child-rearing lead to the depersonalization of the relationship with children. Researcher Jessica Grose outlines the four symptoms:

“You feel so exhausted you can’t get out of bed in the morning, you become emotionally detached from your children, you take no pleasure or joy in parenting, and it is a marked change in behavior for you.”

Work is bad for your health, even working from home

The grim reality is work has always been stressful, even before the pandemic, which has only compounded the inherent stresses of work, from commuting, demanding bosses, and office politics.

Some of these stresses have been minimized because people are working offsite. For example, the modern open office raises stress levels. They are noisy and people are exposed to interruptions and constant observation, if not overt surveillance.

However, working from home is not all sunshine and flowers. There are new stresses that come from the situation, such as dealing with others in the house, like family or housemates. Many started the pandemic with inadequate office gear and insufficient bandwidth. And for many, working and living in the same place meant an abrupt lack of boundaries, both in time and space.

Other stresses came from the disruption of business processes. A colleague canceled a planned call back in March 2020, and I learned later he and his company were evacuated from their building. When I spoke to him a few days later he told me he had just been on a video call to figure out how to onboard new employees virtually, which they had never done before.

Accelerating the adoption of technology is another stress, and the specific difficulties of communicating through the now-ubiquitous video calls instead of face-to-face meetings are a constant irritant, leading to a different sort of burnout.

The hybrid model of work—where people spend some time in the office and some offsite (at home or elsewhere)—leads to new stresses for those working in this style for the first time. Those who work more out of the office may suffer from a fear of being left out, or suffer the consequences of actually being left out, as when managers favor those who are in the office for promotion or better work assignments.

One consequence for some people—such as unmarried employees living alone—is an increase in loneliness, causing stress.

But, in focusing on the individuals suffering from burnout, we are falling into the same failure that many businesses perpetuate: paraphrasing Christina Maslach, none of the strategies that businesses are using to counter burnout will ever be successful if they place all the onus on the worker.

Katy Dineen makes the case that promoting ‘personal resilience’ can be a trap:

“Promoting resilience may be asking employees to remain overly tolerant of unpleasant or counterproductive circumstances. Rather than pushing for change—either through a change of job or fighting for improved workplace conditions—these employees will consistently follow goals once set. Success then becomes the ability to endure stress, and perhaps even abuse.”

Research suggests resilience programs actually have only a small impact, and the results fade over time. Relaxation techniques can counter exhaustion to some extent, but not cynicism and inefficacy.

How businesses fail to counter burnout

According to Gallup, the five primary factors causing burnout are these:

Unfair treatment at work—All sorts of workplace issues can be experienced as unfair: like bias, favoritism, or mistreatment by coworkers or managers. Perceived unfairness leads to 2.3 times more burnout.

Unmanageable workload—Workers who strongly agree they always have too much to do—suffering from unrealistic performance goals, overwork, and lack of work flexibility—are 2.2 times more susceptible to burnout.

Unclear communication from managers—Good managers discuss responsibilities, priorities, goals, and expectations with workers regularly. When these are unclear, employees can become frustrated and exhausted.

Lack of manager support—Managerial support is crucial to burnout prevention. Workers need to know their manager has their back, and those that do are 70% less likely to feel high burnout.

Unreasonable time pressure—Workers who feel they have enough time to accomplish all their work are 70% less likely to experience high burnout. The stress from unrelenting time pressures is negative, and good managers will organize work to avoid it.

The fastest way to counter burnout is to avoid these five mistakes that far too many companies make.

The pandemic has shed a light on some of these stresses, such as business leaders’ demands on remote workers:

“Sixty-seven percent felt they must be available for their employers around the clock, 65% felt overworked, and 63% believed their employers did not want them to take time off from their jobs.“

But many workers are not getting support from managers, as reported by McKinsey:

“Nearly 40 percent of respondents said no one had called to ask, “How are you doing?” No supervisor. No one. And the folks who hadn’t been checked on had a 38 percent higher likelihood of reporting that they weren’t doing well.”

Is the Great Resignation about burnout?

Robert Reich, the former U.S. Secretary of Labor, drew a direct line between burnout and the Great Resignation:

“[Employees] don’t want to return to backbreaking or boring, low wage, sh-t jobs. Workers are burned out. They’re fed up. They’re fried. In the wake of so much hardship, and illness and death during the past year, they’re not going to take it anymore.“

Anthony Klotz, a professor of business administration, coined the Great Resignation term looking into stats about workplace resignations, and seeing the link with burnout:

“A record 42.1 million Americans quit a job in 2019, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, but that rate dropped off during the pandemic-addled year of 2020. As 2021 approached, bringing with it the promise of effective vaccines and a return to semi-normal life, Klotz guessed that two things would happen. First, many of the people who wanted to quit in 2020 but held off due to fear or uncertainty would finally feel secure enough to do so. And second, pandemic-era epiphanies, exhaustion and burnout would drive a whole new cohort of people to quit their jobs. In a moment of inspiration, Klotz predicted that a ‘Great Resignation’ was coming.”

The bottom line on burnout

It may not be possible to make our workplaces burnout-proof, despite my hopes at the outset. The stresses inherent in work and the need to balance making a living and just plain living can’t be minimized to a zero baseline. Still, even though the pressures that working imposes can be moderated many businesses don’t treat work-related stress as a high priority issue, even while trying to stem job turnover and increase productivity.

The first lesson for business leaders is that burnout is endemic: many workers are suffering from burnout, and that is having a negative impact on those people and the business, too.

The second lesson is that any policies that put the onus for burnout on the individual—even if disguised as wellness programs—will fail, and in fact may alienate workers.

The final lesson is that the factors setting the stage for burnout at work are well understood. They all represent the failure of the organization’s management to create a less stressful work environment, one that is more fair and more supportive, where communication is clear, and workers have a reasonable workload and sufficient time to complete their work.It sounds easy when spelled out like that. But clearly, getting this right is very, very difficult. But people’s lives are at stake here, so management must do much, much better.